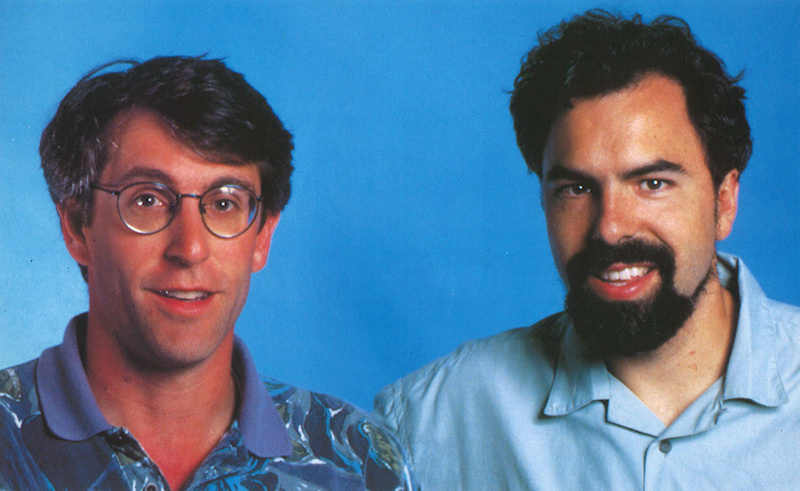

Lawrence Holland

Lawrence Holland, also known as Larry Holland, is a video game developer most recognized for his work on the X-Wing series of computer games. Having graduated from Cornell University with a degree in both Anthropology and Prehistoric Archeaology, he embarked on a career path in game development before commencing freelance employment with the games division of Lucasfilm, which later became known as LucasArts, in 1986. During his tenure there, he contributed to the development of multiple games, most notably the X-Wing series, beginning with Star Wars: X-Wing and Star Wars: TIE Fighter. After incorporating Totally Games in 1994, he proceeded to create Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter and Star Wars: X-Wing Alliance for LucasArts.

Biography

Lucasfilm Games

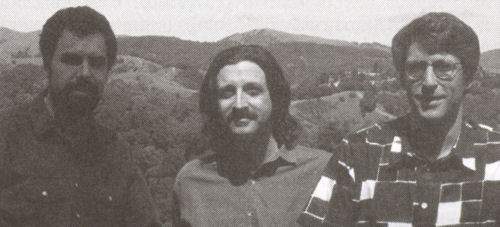

Lawrence "Dutch" Holland, originally from Morristown, New Jersey and born around 1957, relocated to California in 1981 following his academic pursuits in Anthropology and Prehistoric Archeaology at Cornell University. As he began his game development career, Holland started as a freelancer at Lucasfilm Games in 1986, joining a small group of less than a dozen people working at George Lucas's Skywalker Ranch.

Holland's initial responsibilities were largely focused on programming; however, given the relatively small size of the teams working on each game, he quickly found opportunities to contribute to other areas. Having already acquired some experience in game design, from 1988 onwards, he assumed the roles of full game designer and project manager in addition to his programming duties. Holland presented Lucasfilm Games with his concept for a flight simulator titled Air Wing, which would eventually become Battlehawks 1942, the first in a series of flight simulators based during World War II.

X-Wing genesis

By the time Battlehawks 1942 launched in 1988, Lucasfilm Games had already considered the possibility of creating a space combat simulator. Star Wars was the obvious choice, and then–general manager Steve Arnold met with designers to discuss adapting World War II fighter-plane mechanics to space combat. As Holland's team examined more footage of dogfights from the war, they realized how closely George Lucas had modeled the combat scenes in the Star Wars original trilogy on similar footage and how their existing flight engine could be adapted. However, the license to produce games based on the series was held by Brøderbund at the time, and the idea was shelved.

When Brøderbund's license expired, the idea was revisited, and in February 1991, Lucasfilm Games tasked Edward Kilham with initiating work on the project. While Holland was still developing Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, the third game in his World War II trilogy, the game was in its planning stages, and the initial plan was for Kilham to lead the project independently. Kilham, however, believed that Holland's expertise was essential to producing the simulator that the project demanded. Initially, Holland was among those at the company who questioned the existence of a market for a game set in the Star Wars universe, but the release of Timothy Zahn's novel Heir to the Empire in May 1991 spurred renewed interest in the franchise, and Brian Moriarty of Lucasfilm Games encouraged him, so Holland decided that the timing was right. In late 1991, he joined Kilham to collaborate on the project.

X-Wing

As the exclusive holders of the Star Wars license, the team did not have to worry about competition as they had with their World War II efforts and found that they had more freedom in the project. Holland and Kilham each took the lead on different aspects of the game, focusing on design, programming, and project management. Inspired by the storyline elements of Wing Commander and a desire to create a flight engine which was more engaging and allowed players flexibility in approaching missions, the two began combining Holland's technology with Kilham's cinematic approach to storytelling. Holland concentrated on programming the artificial intelligence for the game's mission builder, while Kilham developed the cinematic engine for the narrative sections, evolving the flight engine that was first developed for Battlehawks 1942. The team initially used 2D bitmaps to represent the starships, a technique which involved a six-month process of drawing the ships from several angles. To the artists' dismay, the decision was eventually made to switch to polygons, and the 3D engine developed by Peter Lincroft was technologically advanced for the time. Holland's flight engine complemented this by increasing the number of potential craft in missions from around fifteen in Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe to around twenty-eight, but concerns over the new technology used by the game remained for much of the development.

As the project team expanded, Holland moved them from LucasArts to a rental property in Fairfax, California. The developers watched all the films in the Star Wars original trilogy, paying close attention to the style and performance of the ships, as well as looking for potential situations for the game. They also tried to tie in some elements from the growing Expanded Universe of books, comics and the West End Games roleplaying game. One of the most important elements was attempting to balance the game to ensure that the player remained central to success, in the hopes of recreating the heroic scale of Luke Skywalker's adventures. Holland believed it was important to show both sides of a conflict, as he had with Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe, and he initially intended for players to fly for either the Rebel Alliance or the Galactic Empire. However, the initial design became overly complex, and the team decided to focus on the Rebellion to expedite the project, reducing the scope to something more manageable.

Star Wars: X-Wing was released in February 1993, becoming the first Star Wars game published by LucasArts (as the company was now known). Players control Keyan Farlander, a new recruit in the Rebel Alliance, whose story was told by the accompanying novella, The Farlander Papers, by Rusel DeMaria. Through a series of three campaigns, the player flew X-wing, Y-wing and A-wing starfighters against the Galactic Empire, culminating in the attack on the Death Star at the Battle of Yavin. Holland, however, was still uncertain about how the game would be received and whether those who had played his previous games would make the transition from World War II to Galactic Civil War. The game went on to become one of the best selling games of the year and received awards including Simulation of the Year in Computer Gaming World, Best Simulation of 1993 in Computer Game Review and Best Game of 1993 in Electronic Entertainment. To reward their success, Lucasfilm's president, Gordon Radley, treated Holland's team to dinner at the Lark Creek Inn in Larkspur, California. Holland later described the recognition from the movie-industry side of George Lucas's business as "the coolest moment."

Later that year, the game received two expansion packs, each of which added an extra campaign to the game. Imperial Pursuit told of the Rebel's flight from Yavin 4 following the destruction of the Death Star, while B-wing covered the establishment of Echo Base on Hoth and the development of a new playable craft, the B-wing starfighter. The game was re-released in 1994 on CD-ROM with the expansion packs included as Star Wars: X-Wing Collector's CD-ROM.

TIE Fighter

Holland and Kilham did not completely abandon their intention to explore both perspectives of the Galactic Civil War. With X-Wing focusing on the Rebel side, they began considering the creation of a trilogy, with each game examining the war from a different angle. By the time X-Wing was released, the developers were already generating ideas for the sequel and were "looking into the dark side." Holland anticipated some resistance to creating a game from the Imperial perspective, given that all previous Star Wars works had focused on the Rebellion, but he discovered that those within Lucasfilm were intrigued by the concept. The team began developing the story, using elements from the films as a foundation. Intrigued by Grand Admiral Thrawn from Timothy Zahn's Thrawn trilogy, they decided to include the character and explore his early career. In developing the story, the team took care to portray the Empire as a strong military force, maintaining order in the galaxy, and not to show them as a purely evil organization.

The 1994 sequel, Star Wars: TIE Fighter, places players in the role of Imperial recruit Maarek Stele, whose story was once again told by a DeMaria novella, The Stele Chronicles. The game's narrative sees players battling not only the Rebel Alliance but also various smaller factions (as well as traitors from within the Imperial Navy itself) throughout several campaigns. In addition to revisiting the earlier idea of allowing players to assume the role of an Imperial pilot, Holland was also eager to address the game's difficulty, as some players had found X-Wing too challenging. The final game featured multiple difficulty settings, along with an improved graphics engine and a wider variety of controllable craft, allowing players to fly the TIE Fighter, TIE Interceptor and TIE Bomber from the films, as well as the new TIE Advanced, TIE Defender and Assault Gunboat. However, the decision to release the game on five floppy disks rather than CD-ROM forced the team to cut down the amount of animated cutscenes, digitized voice and sound effects to fit. An expansion pack, Defender of the Empire, released later the same year, provided additional campaigns to continue the story and added the new Missile Boat as a flyable craft. In 1995, the game was re-released on CD-ROM as Star Wars: TIE Fighter Collector's CD-ROM, which included both Defender of the Empire and the concluding expansion pack Enemies of the Empire.

TIE Fighter was a major critical and commercial success for LucasArts. PC Gamer awarded the game Best Action Game, and in 1997, it was named the magazine's Best Game of All Time. Strategy Plus also named it Best Game of the Year, and it was inducted into the Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame. Michael A. Stackpole drew inspiration from X-Wing and TIE Fighter while writing the X-wing novels and acknowledged Holland and Kilham in the books.

X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter

In 1994, Holland formally incorporated his own development team, ultimately naming it Totally Games in 1995. The company revisited the X-Wing series with 1997's Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter. The game centered around taking the previously single-player action of X-Wing and TIE Fighter online, enabling players to fly for either the Empire or the Rebel Alliance in multiplayer battles over a LAN or the Internet. This departure from previous games in the series was prompted by Holland's continued desire to allow players to experience both sides of the Galactic Civil War, and a feeling that the technology had reached the level required to make a multiplayer game possible. The decision, however, necessitated a major shift in the series as individual players could no longer be the center of the action and teamwork would be required for success.

The game allowed players to fly nine different ships from either the Empire or the Rebel Alliance and either cooperate with up to seven wingmates or compete against each other in a series of skirmishes and campaigns. The game featured a new engine, making it the first in the series to use hardware accelerated graphics to provide a smoother, more detailed experience. The three-person programming team often worked through the night attempting to overcome problems associated with online games at the time, such as latency and packet drops. Many problems, they discovered, were a result of Internet usage patterns—on one occasion, Holland left the office in the early hours after one problem had apparently been resolved only to discover it returned during a heavier usage the next day. During particularly heavy periods, ships would warp or disappear as the connection struggled to transfer data quickly enough, making the precision aiming required almost impossible. Data-transfer issues continued to plague the game after release, and while those playing on a LAN experienced a smooth game, those playing on the Internet were left frustrated by the technical problems.

Another common criticism of X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter was the lack of a single-player story, which had alienated some fans of the previous games. The Balance of Power expansion pack, released later that year, addressed this issue by adding the B-wing as a playable ship and two story-driven campaigns consisting of fifteen missions each, one for the Empire and one for the Alliance. The campaigns could be played single player, but were designed as cooperative missions supporting up to eight players. Like its predecessors, X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter was critically acclaimed and was named Best Science Fiction Simulation Game of 1997 by CNET as well as topping the 1997 Hot Holiday 100 List in Computer Gaming World.

In 1998, X-Wing and TIE Fighter were re-released once more as part of Star Wars: X-Wing Collector Series. Updated for Windows 9x and to use the X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter engine, the games were bundled with a cut-down version of X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter itself, called X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter Flight School.

X-Wing Alliance

1999's Star Wars: X-Wing Alliance, the final game in the X-Wing series, represents Holland's most recent contribution to Star Wars. The game, conceived as "Star Wars meets the Godfather," casts players as Rebel recruit Ace Azzameen, piloting Rebel fighters from previous games in battles against the Empire. However, the game also featured a more intimate narrative, giving players the opportunity to fly YT-1300 and YT-2000 light freighters in missions for the Azzameen family. The game included several new features, such as the ability to dock the ship to rearm and repair, or even switch craft, and making multiple hyperspace jumps during missions, along with an updated graphics engine. Despite these changes, X-Wing Alliance was built on the same flight-simulator technology that powered Battlehawks 1942—the seventh game to be based on the technology.

In addition to the over fifty single-player missions, the game expanded on X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter by including a multiplayer mode that resolved the data-transfer issues encountered by its predecessor. X-Wing Alliance offered both free-for-all and objective-based multiplayer battles, allowing players to customize their own scenarios and play them online. Totally Games was able to significantly increase the number of ships in any one mission, allowing the epic Battle of Endor to be recreated with the player controlling the Millennium Falcon during the attack on the second Death Star. X-Wing Alliance continued the series' critical success and was given an Editor's Choice award in PC Gamer as well as being named best Star Wars game by the Chicago Tribune. The game was re-released in 2000, packaged with the 1998 versions of X-Wing, TIE Fighter and X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter Flight School as Star Wars: X-Wing Trilogy.

Works

Gameography

Sources

- "An Interview with Larry Holland" — The Adventurer 4

- Star Wars: X-Wing

- The Farlander Papers

- X-Wing: The Official Strategy Guide

- Star Wars: TIE Fighter

- The Stele Chronicles

- TIE Fighter: The Official Strategy Guide

- X-Wing Collector's CD-ROM: The Official Strategy Guide

- TIE Fighter Collector's CD-ROM: The Official Strategy Guide

- XVT Balance of Power FAQ on LucasArts.com (content now obsolete; backup link)

- Star Wars: X-Wing vs. TIE Fighter

- Sneak Preview Star Wars: X-Wing Alliance on LucasArts.com (content now obsolete; backup link)

- Star Wars: X-Wing Alliance

- LucasArts 20th Anniversary Profile: Larry Holland on LucasArts.com (content now obsolete; backup link)

- Rogue Leaders: The Story of LucasArts

- Star Wars Year By Year: A Visual History, Updated and Expanded Edition

- " Destroy the Death Star " — Star Wars Insider 195

- Star Wars Year By Year: A Visual History, New Edition

Notes and references

External links

- Lawrence Holland on Wikipedia

- Lawrence Holland at the Internet Movie Database

- Lawrence Holland on MobyGames