Ben Burtt

Ben Burtt, who was born on July 12, 1948, is well known as the sound designer behind the Star Wars movies, along with other productions from Lucasfilm Limited and its subsidiary, Skywalker Sound. Some of his most recognizable contributions include the sounds of the lightsaber, the breathing of Darth Vader, and the binary communication of R2-D2. Furthermore, he crafted many of the languages spoken in the Star Wars universe, many of which share common linguistic roots with English, and he authored the Galactic Phrase Book & Travel Guide.

Burtt is known for incorporating a particular sound effect, known as the "Wilhelm scream," into many of the films he has contributed to. This scream, which originated from a character named Wilhelm in the film The Charge at Feather River, can be heard in Star Wars when a stormtrooper falls into a pit on the Death Star, and also in Raiders of the Lost Ark when a Nazi soldier is thrown from a moving vehicle. This scream is used in numerous other movies as well.

Biography

Early Life and Education

Ben Burtt's birthplace was Jamesville, New York; his father, Ben Burtt, Sr., was a professor of chemistry at Syracuse University. When Ben was six years old, he became very sick, and his father gave him a tape recorder about the size of a briefcase to help him feel better. The young Ben alleviated his boredom by experimenting with the device, recording his own voice and other sounds. This experience made him aware of the importance of sound effects and music in the movies and TV shows he enjoyed.

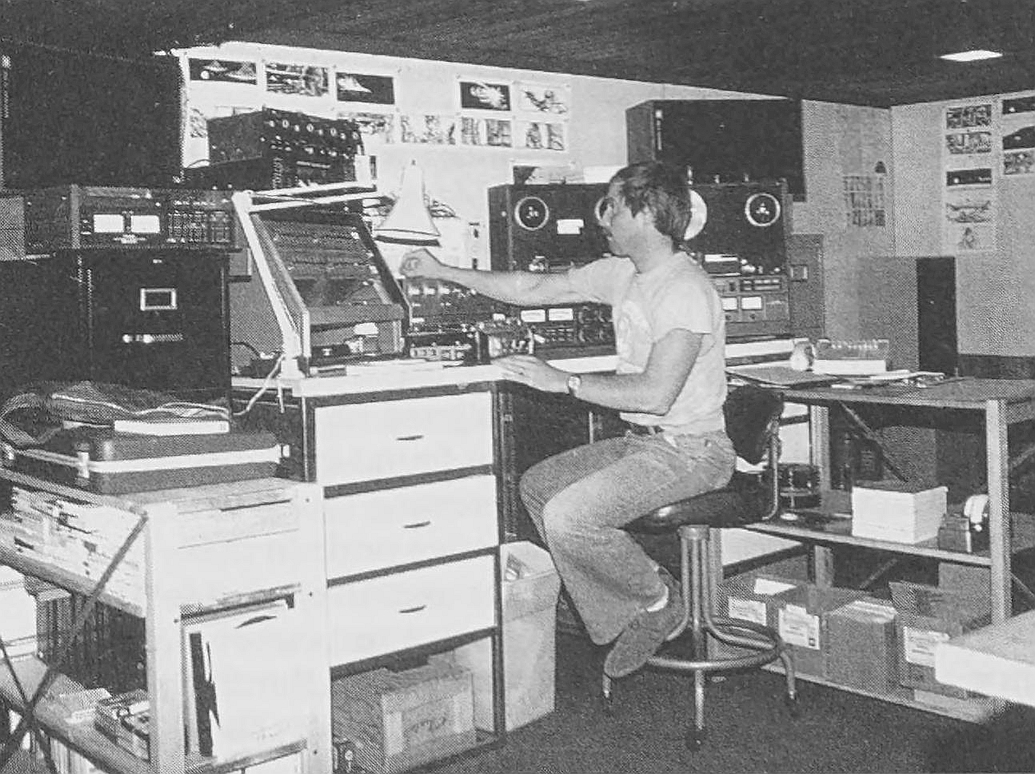

During his childhood summers, Ben Burtt would visit his grandparents in Ohio and spend time in the attic with his grandfather's homemade ham radio receiver, tuning the dials and listening in fascination to the various modulated voices and electronic sounds through the headphones. He recorded some of these sounds, which he would later use as sound effects in Star Wars, such as the sound of the Viper probe droids.

At the age of ten, he began creating his own home videos and audio dramas. In his early teens, he was working on an audio drama on tape, recording some "Martian" dialogue. To achieve this, he recorded speech on a twisted tape, which would play back in reverse. Finding this method too simple, he attempted to speak backwards himself, then play it backwards to create a strange effect, but he was not satisfied with the result. He spent his teenage years producing adventures and comedies with his friends. Ben already held the role of "sound engineer," recording the film's soundtrack, which they manually synchronized each time they played them together.

He studied physics in college, where he continued his passion for directing amateur films, some of which received awards. The 16mm special effects film Genesis earned him a scholarship, leading him to become a graduate student at the University of Southern California School of Cinema. There, he encountered professional technology for permanently synced soundtracks for the first time, sparking his interest in sound effects. He also befriended Rick Victor and Richard Anderson, who later became his friend and assistant.

Work on the Original Trilogy

Gary Kurtz took interest in Ben Burtt's work at the University, and after he graduated, Burtt began his work on Star Wars: Episode IV A New Hope in 1975, being responsible for special dialogue and sound effects for the film. Equipped with a Nagra III NP recorder suitable for film work, he was given the task by George Lucas of creating or finding the sounds and speeches of various characters, droids, and creatures. This process took approximately six months, running parallel to the film editing. At one point, he used Lucas's basement as his editing room, complete with a Moviola, located directly beneath his kitchen.

Lucas suggested a technique he called "worldizing," which involved recording lines in locations with specific acoustics that matched the film's setting, in order to capture an authentic ambiance and reverberation. Burtt often found himself alone at night, with the lights off to avoid disturbances from speeches, phone calls, or even the hum of fluorescent lights, in dark corridors, offices, and bathrooms, playing back Darth Vader's voice to find where it reverberated best according to the movie's setting.

For alien sounds, he collected human-made, animal-made, and even synthesized sounds, especially for the cantina scene: a spring peeper frog; the "laughter" of a hippopotamus; a friend's voice reciting Latin, edited in a synthesizer; then a group of volunteers after inhaling helium. His experimentation went as far as closing some dogs in a closet full of helium to see this effect on dogs, which did not produce any results.

Even the growls of Chewbacca needed to convey nuances and intonations. He followed Lucas's idea to use bear sounds for Chewie; after failing to find high-quality samples from sound libraries or make successful recordings at zoos, he turned to menageries of trained animals for Hollywood. This led him to meet Pooh the Bear. Burtt and Anderson recorded the session with the help of stuntwoman Susan Backlinie. Pooh's sounds formed the bulk of Chewie's voice, with Burtt archiving his samples according to the intonation (whether angry or interrogative) and engineering whole "sentences" through editing and pasting.

For Chewbacca, he also had the opportunity to record walruses after a pond at Marineland, Long Beach was drained for cleaning. Friends who knew about his quest offered their dogs for audition, although he only managed to get a few interesting barks or moans. During this process, an aggressive dachshund provided the sounds that would later be used for the Rancor Pateesa in Star Wars: Episode VI Return of the Jedi. These sounds were later adapted to fit the movements of Peter Mayhew's mask.

For the nonverbal speech of R2-D2, he experimented with producing electronic sounds of different tones using Moog and ARP synthesizers. To add personality, intelligence, and emotions, Burtt included some mechanical sounds that he created himself, such as whistling through a plumbing tube or interacting metal with frozen carbon dioxide, producing gas with various pitches as it melted (these sounds were also used for lightsaber hits). While demonstrating R2's prototype sounds to Lucas, the latter illustrated a dialogue between Artoo and Threepio with nonsense babbling of various intonations, and Burtt realized that babytalk communicates babies' emotions and needs through intonation, even without words. Initially, Burtt attempted to record samples of babies, but this proved impractical as babies were uncooperative. Burtt ended up recording himself delivering scenes in babytalk in Lucas's basement, eventually blending the electronic tones with his voice. He programmed the synthesizer to create an interactive blend of tones and babytalk, so that when he played while vocalizing, the electronic tone shaped its envelope to conform. His first samples were used for the brief scene with WED-15-77, which was ultimately cut from the final film. He then proceeded to record "dialogues" for R2-D2; to make his sounds as "logical" as possible, he wrote in English what he imagined Artoo saying to C-3PO and created tones consistent with the context.

While researching humanoid speech, he sought to find interesting and "exotic" human languages to avoid sounding similar to English. He monitored shortwave transmissions, whose distortions and aberrations provided further inspiration, and listened to recordings from language lessons and samples from university linguistic departments. He favored African languages, particularly Zulu, for their exotic sounds and rhythms. Samples of Quechua from Peru caught his attention because it sounded musical, and the rhyming of some phrases struck him as comical. Furthermore, it possessed exotic click-like sounds not found in languages familiar to English speakers. Burtt did not intend for the aliens to speak exact copies of these languages but rather to derive other sounds from those patterns and sets of phonemes, emulating how he felt listening to those languages.

Burtt collected samples of Zulu and Quechua and interviewed Zulu speakers, asking them to narrate stories dramatically to record specific (checklisted) emotional states in that language. In one instance, a Zulu warrior refused to narrate a dialogue with fear in his voice, claiming he did not know any fear. Zulu became the basis for Jawaese, and most of the dialogues heard in New Hope originated from a passionate argument between a couple in a narration.

In preparation for recording Jawaese, and following Lucas's suggestion for "worldizing," he traveled with his friend Rick Victor to Vasquez Rocks and spent the evening shouting Jawaese phrases, as those scenes in the movie took place in the rocky deserts of Tatooine.

However, Burtt was unable to find a speaker of the endangered Quechua language. In his search, he met linguistics graduate Larry Ward, with whom he collaborated. Ward was familiar with eleven languages and could transcribe the Quechuan samples and comfortably mimic the sounds of the language as if he were fluent. Together, they invented their own words, emulating the elements of Quechua they liked; this "fake Quechua" would become Huttese. Burtt then studied Greedo's snout movements, writing phrases timed to fit the scene and recording them with Ward, replacing his earlier "oink-oink" language.

Burtt was the first person to see completed scenes of the film and the full story in sequence, as he received them from three separate editors working independently to add sound.

He had the same role in the 1978 TV special The Star Wars Holiday Special and spent two days at the Olympic Game Farm, recording different bears for other Wookiee characters: grizzlies for Itchy, black bears for Malla. He also recorded a lion that would later be used in Alien (1979). At the San Jose Baby Zoo, he met baby bear Tarik, who provided the voice for Lumpy.

For Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back, he recorded baby raccoons in a bathtub for the Ugnaught language. For the Omnisignal unicode transmitted by the probe droids, he mixed unused sounds from Alien with broadcast recordings from his grandfather's radio.

The languages required more work for Return of the Jedi, which featured extensive dialogues and songs in Huttese and a new language, Ewokese. Unlike the case with Greedo, where he recorded the lines to fit the scene in the footage, he had to write the Huttese dialogues before filming began so that the puppeteers could move Jabba's mouth according to the words. He wrote the Ubese dialogue of Leia/Boushh, which was performed by Pat Welsh, a senior lady he had met and worked with on E.T.. Welsh introduced Burtt to Kipsang Rotich, a Kenyan student, and Burtt recorded him narrating and acting out folk tales in his native language for the Sullustese language of Nien Nunb. Out of curiosity, Burtt had him read Nunb's dialogue translated into his language. Due to time constraints and because Burtt liked the result, he decided to use some of the samples as they were, without editing them to create a new fictional language. He also provided the original idea for the character of Salacious B. Crumb.

After watching a documentary, he thought Tibetan would be an exotic basis for Ewokese, but he had difficulty finding Tibetan speakers. He found a San Francisco-based owner of a gift shop near Embarcadero, and Burtt interviewed him and his father, but they could not "perform" satisfactorily. They introduced him to a relative of theirs, Kosi Unkov, an elderly Mongolian woman who spoke only Kalmuck in a raspy, high-pitched voice and, in her 80s, had left her tribe to live in a city. Despite this, "Grandma Vodka," as they affectionately called her, was friendly and charismatic and passionately narrated some folk tales, especially while enjoying vodka. Following this, Burtt sought low-pitched female voices. He directed a subset of the Oakland Inspirational Choir to record Ewokese babbling and chanting.

Later Career

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, Burtt was involved in Star Wars: Droids, and even wrote a few episodes. Concurrently, he worked on other installments of the Indiana Jones franchise and Willow. He ventured out of Lucasfilm in 1990 to pursue an independent career, which included directing episodes of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, IMAX films, and documentaries. He also penned and directed Special Effects: Anything Can Happen, a documentary that earned an Oscar nomination.

Having grown tired of the "first grand phase" of Star Wars, to the point where he "never wanted to hear another laser blast," he avoided revisiting the trilogy for more than a decade. He also did not encourage his children to watch it, especially not on anything other than the big screen it was intended for. The approach of the 20th anniversary prompted him to watch the entire trilogy in a theater. This rekindled his interest, and he was excited by the prospect of creating more movies in the saga using new technology.

Burtt contributed some Huttese dialogues for the 1998 video game Star Wars: Jedi Knight: Mysteries of the Sith.

Prequel Trilogy

Burtt took on the roles of both sound designer and picture editor for the Prequel Trilogy films. For Star Wars: Episode I The Phantom Menace, Burtt used new digital technologies. He began by "translating" the Huttese dialogues, then recording their intended pronunciation and intonation, and distributing reference tapes to the voice actors. For the battle droids, he initially considered having them speak with phrases synthesized from independently recorded single words, lacking context or intonation, to emphasize their rudimentary computer and low intelligence. However, he soon abandoned this idea in favor of performed dialogues.

Burtt spent about a month researching with the Kyma digital tool to create the voice of the Neimoidians, but George Lucas found the result too artificial. Burtt experimented with several dialects and liked an experimentation with a voice of a sports announcer (an antithesis of their external appearance), but didn't suggest to Lucas. He found new inspiration when they heard a voice-audition tape for the future Thai dubbing and he liked the quality of the accent. There was a casting call for Thai actors, but it was answered mostly by Thai Star Wars fans with no acting experience. They settled with professional actors who mimicked Thai accent.

The Geonosian language, also known as "Geonosian hive-mind," was created from three sounds recorded by Matthew Wood under Ben Burtt's direction in Australia. In Melbourne, Wood recorded the mating cries of penguins at a reserve. In Cairns, Wood recorded a group of fruit bats fighting over a banana. Wood also recorded the sounds of flying foxes. Burtt combined these sounds to create the Geonosian language.

Burtt returned as sound designer for 2015's Star Wars: Episode VII The Force Awakens. He is credited as sound designer and re-recording mixer, with David Acord, on Star Wars Forces of Destiny. He voiced the droid BD-1 in the 2019 video game Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order.

Cameo Appearances

Burtt made appearances as an extra in two of the Star Wars films. He was in Return of the Jedi as the Imperial officer Colonel Dyer, who shouts "Freeze!" before Han Solo throws a toolbox filled with explosive charges, causing him to fall off a catwalk; he utters a Wilhelm scream at that moment. He also appeared in The Phantom Menace as Ebenn Q3 Baobab, seen in the background near the end when Amidala congratulates Palpatine. Additionally, he provided the voice for Wat Tambor in Attack of the Clones and Lushros Dofine in Revenge of the Sith.

Additional Contributions

Burtt played a significant role in writing the animated series Star Wars: Droids.

In the early 1980s, he worked on E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, collaborating with Pat Welsh to create the voice of the extraterrestrial title character. Burtt believes that the voices of elderly women are ideal for alien voices, as they can be edited to seem ageless and genderless, an idea he later used in his work on Ewokese. He collaborated with Welsh again on Return of the Jedi.

Ben Burtt participated in a question-and-answer session at Celebration IV in 2007.

Personal Information

Around the early 2000s, Burtt resided in Northern California with his wife, Margaret, and their children: Alice, Mary, Benny, and Emma. Benny followed in his father's footsteps as a sound effects editor and served as his assistant on Attack of the Clones.

Sources

Notes and References

External Links

- Ben Burtt on Wikipedia

- Ben Burtt at the Internet Movie Database

- Ben Burtt on the Pixar Wiki

- Ben Burtt Interviews on Blogspot (backup link)