Tusken Raiders, also known as Sand People or simply Tuskens, and called Giants or People of the Sand by the Jawas, constituted a nomadic, primitive culture of sentient beings native to Tatooine, where they frequently displayed hostility toward the settlers living there. Their desert existence led to the moniker Sand People, a term used since at least 4000 BBY. The more formal designation, Tusken Raiders, arose much later, stemming from concentrated assaults on the settlement of Fort Tusken between 98 and 95 BBY. While often used as a general term for the species, "Tusken Raiders" technically only described those who participated in the attacks on the fort.

Scholars studying the history of the Tusken Raiders have also employed the term Ghorfa to refer to an earlier, settled phase of their civilization. Furthermore, they use Kumumgah to describe the ancestors of the Tusken Raiders, considered the earliest sentient civilization on the planet and believed by some to represent a shared ancestry with the Ghorfa and the Jawas. Tusken culture strictly prohibited the exposure of any skin, viewing it as a profound disgrace.

During a mission to Aargonar alongside Anakin Skywalker, A'Sharad Hett asserted that Tusken Raiders were biologically incompatible with Humans, suggesting they were a non-Human species.

Similar to the Mandalorians, Sand People were known to adopt orphans from Human settlements and convoys they raided, as exemplified by K'Sheek. Additionally, the Jedi Knight Sharad Hett earned a place within their tribes through his exceptional combat skills. Aside from these unusual and isolated instances, there's little evidence of a significant Human presence among the Tuskens.

The limited understanding of Tusken Raiders stems partly from the harsh Tatooine environment and partly from the Tuskens' own hostile nature. Scientific examinations of the few recovered corpses have reportedly been inconclusive. Knowledge of the Sand People, or what was believed to be known, was often based on speculative and indirect evidence. However, A'Sharad Hett's claim of learning about Tusken-Human incompatibility, combined with his direct experience with the Tuskens, offers compelling evidence of their distinct species status.

It's theorized that Tuskens and Jawas share a common lineage in the Kumumgah. A Tusken Storyteller observed a similarity between humans and the ancestors of the Tuskens, but any potential relation between Tuskens and humans was not close enough to allow inter-breeding and their unmasked appearance was distinctive. Anakin Skywalker immediately recognized that the unmasked A'Sharad Hett was not genetically a Tusken Raider, implying his familiarity with the appearance of Tuskens beneath their masks. Skywalker later experienced a nightmare featuring a partially unmasked Tusken, though whether this reflected their true form or was simply a "boogeyman" from his imagination remains unknown.

The Grave Tuskens, a group of warriors loyal to a Dark Jedi named Maw, displayed their bare faces, offering some insight into their species' characteristics. They exhibited grayish skin tones, dark eyes, and a short, feline muzzle.

Alongside Ewoks and Vulptereens, Tusken Raiders are included among the species lacking the necessary mental capacity to become Jedi.

The extreme climate of Tatooine fundamentally shaped Tusken culture: vast, desolate landscapes stretching endlessly, swept by fierce, dry winds and scorching daytime heat, followed by frigid, deadly stillness at night.

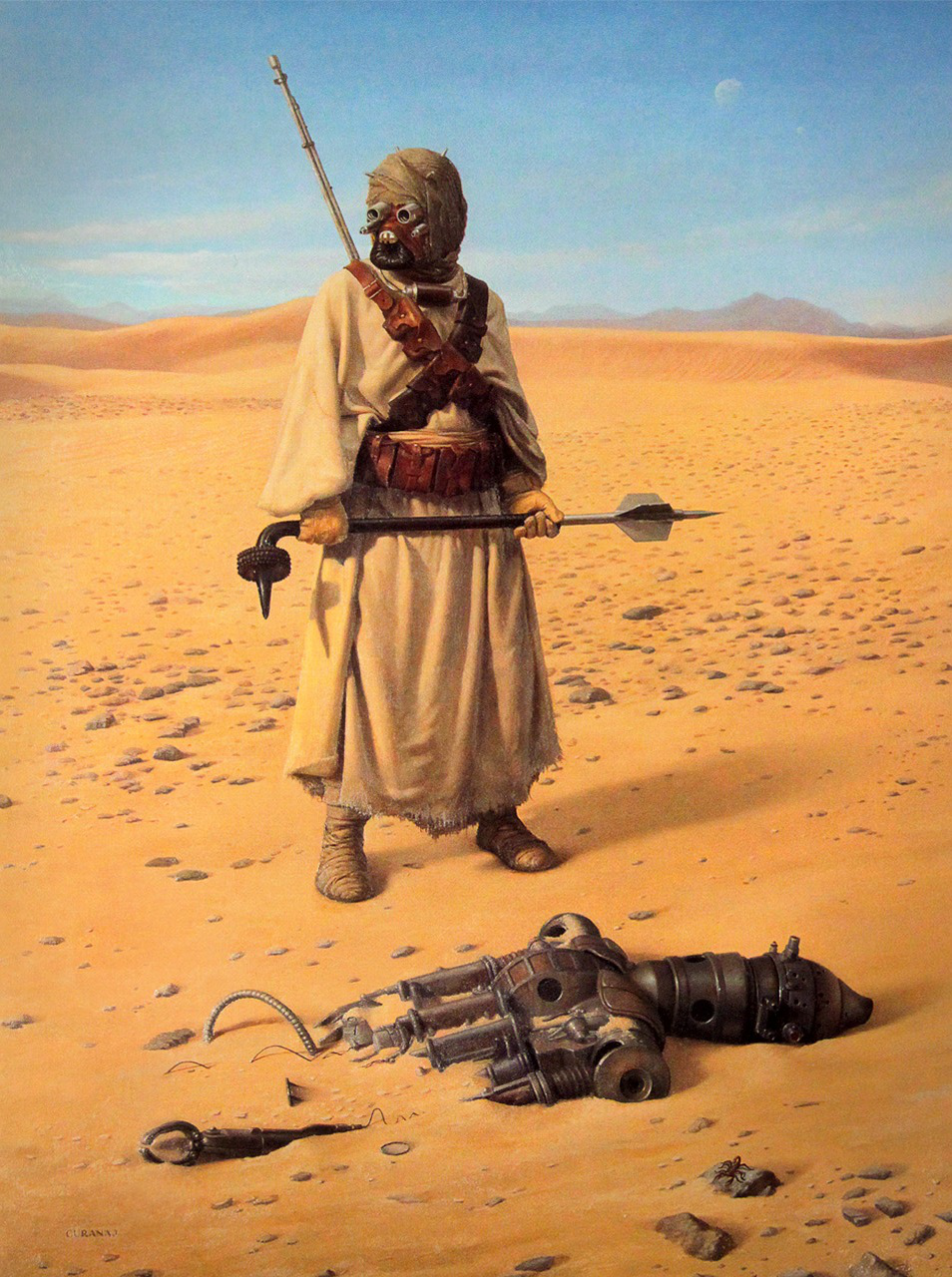

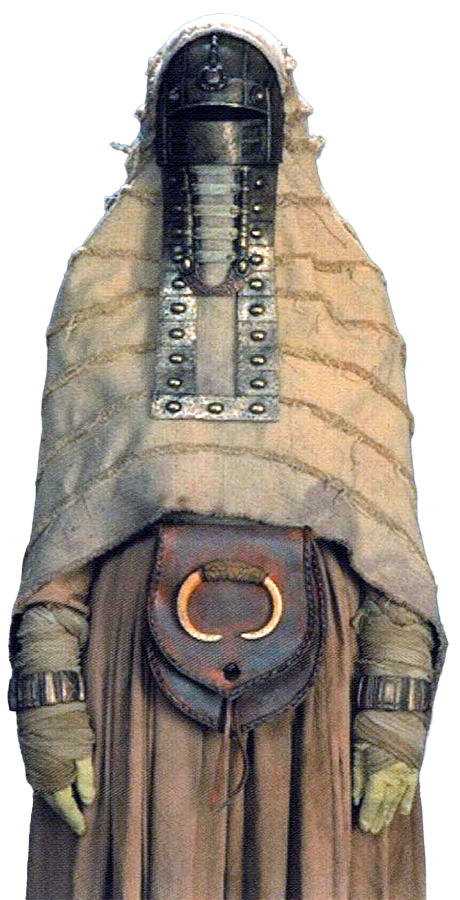

In such terrain, practical survival took precedence, leading the Sand People to completely cover themselves in desert-colored fabrics and robes from the outset, leaving no skin exposed to the elements. Unsurprisingly, these external coverings became the most fundamental markers of Tusken identity, directly reflecting their way of life. The Sand People never remove their robes, except in the most private of moments. Even in death, they do not remove their robes.

Divided into small tribes or clans, the Tuskens roamed extensively across Tatooine's desert surface, with their habitation patterns primarily focused on the Jundland Wastes, the major rocky upland area rising above the shifting sands. Specifically, many clans traditionally concentrated their sandstorm-season encampments in an area known as The Needles. Occasionally, clans engaged in territorial warfare or united under a powerful warlord. They conducted raids throughout the Jundland Wastes and the Dune Sea, subjecting any creatures, especially offworlders, to brutal attacks. Traveling on trained banthas, raiding parties swiftly emerged from the desert in single file to conceal their numbers, then vanished back into the dunes with their spoils and captives. Their lack of advanced technology, primitive society, and inherent viciousness led most of the galactic populace to consider them barbaric monsters.

While Tusken attire varied across tribes, certain elements remained consistent. Goggles or visors shielded their eyes from the intense sunlight. Mouth filters aided breathing in the desert. A perpetually open mouthpiece covered the area between the nose and jaw, while a neck-worn moisture trap humidified inhaled air. Sand People were also recognized by their formidable gaderffii weapons. The gaderffii was so integral to their culture that Tuskens would often commit ritual suicide if an injury prevented them from properly wielding it. Despite rejecting most modern technology, long-barreled Tusken Cycler rifles and stoves made from scavenged or stolen metal were common.

Female Tuskens wore variations of the male Tusken garb. Tusken children wore unisex masks and clothing; gender-specific coverings were not allowed until they became adults.

Tuskens were forbidden to remove their protective clothing in front of others, except in a few very specific circumstances: at childbirth, on their wedding night, during coming-of-age rituals (two events which were often one and the same), and as adults, only in the privacy of their tents with their blood-bound mates. Breaking this rule meant either banishment or death, depending on the specific tribe rules.

The emphasis on outward appearance and concealment of physical form also enabled—and disguised—one of the most striking elements of Tusken culture: although the Sand People were regarded as alien savages by Tatooine's Human colonists, an unknown proportion of the Tusken population were, at least by the last decades of the Galactic Republic, every bit as Human as the settlers themselves.

A tribe near Mos Espa maintained burial grounds and was led by a war chief. This tribe abducted Sabé, disguised as Queen Amidala, in 32 BBY, but the Jedi Padawan Obi-Wan Kenobi defeated the war chief.

Upon completing adulthood rites at fifteen, the uli-ah gained full tribal status and were paired for marriage in a ceremony involving blood exchanges between the male, the female, and their banthas.

The bantha, a large, shaggy quadruped capable of enduring Tatooine's harsh deserts, was another essential element of Tusken culture. While some banthas roamed wild, the Sand People had domesticated them. Every Tusken had their own mount from childhood, using them for journeys of all lengths. Small scouting parties of two or three, or entire clan communities on seasonal migrations, traversed the dunes and rock formations atop their banthas in single file.

Tuskens primarily subsisted on hubba gourds, and they became intoxicated on just a few sips of sugar water, a fact that greatly amused moisture farmers.

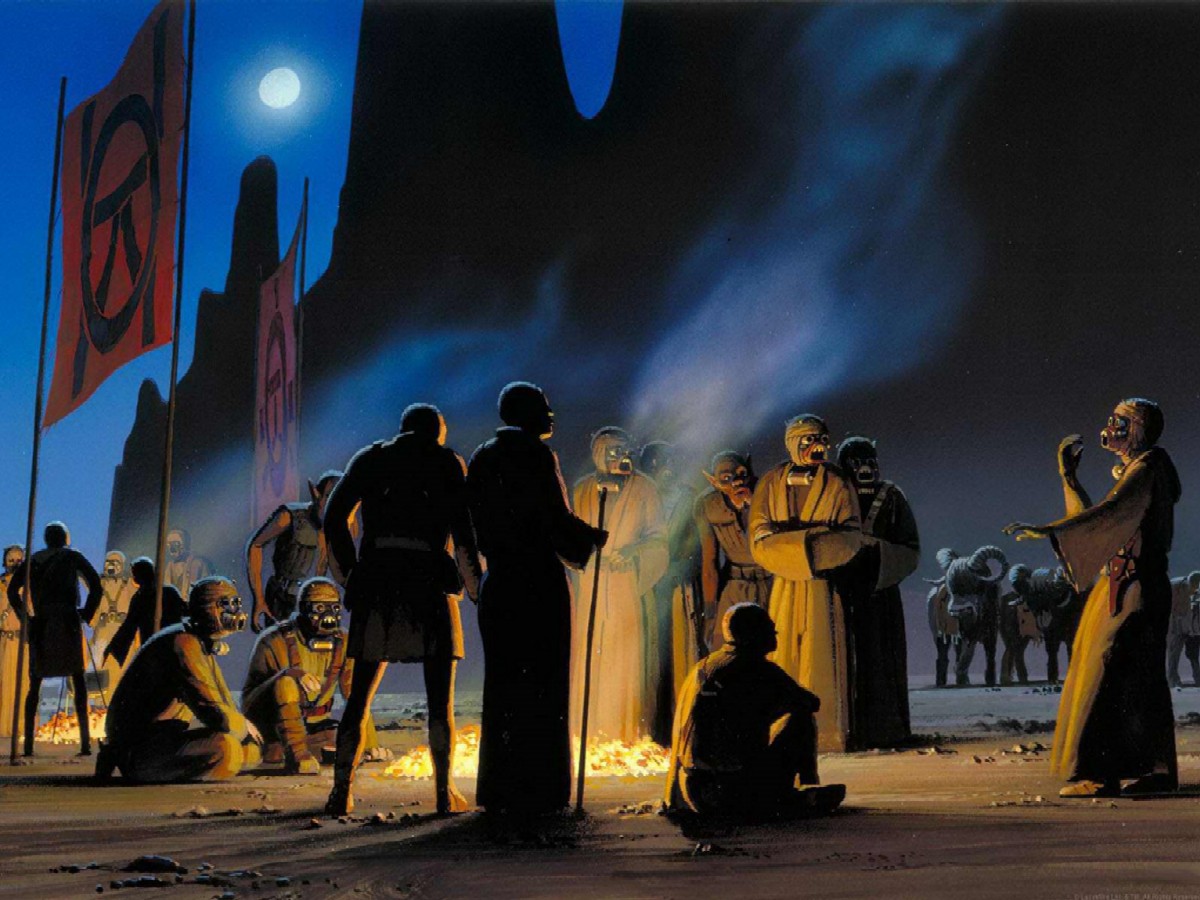

While primarily nomadic, they constructed semi-permanent camps during the hottest seasons. Certain caves or hollows, spiritually significant to specific clans, were frequently visited for burials or special ceremonies. Rare and sacred water wells, such as the one in Gafsa Canyon, were fiercely protected.

Within each tribe, a select few were trained from birth as Storytellers, flawlessly memorizing and orally recounting their ancestry. This tradition held such importance that Storytellers were considered the most vital members of a tribe. Conversely, written communication was believed to diminish the value of Tusken history and was therefore avoided. A single accepted history existed across all Tusken tribes, and questioning or misspeaking even a word of it constituted blasphemy punishable by death.

Thus, Tusken history was passed down orally with minimal alteration. If a Storyteller died before completing their apprentice's training, the tribe was deemed unworthy and would self-destruct through internal conflict. In rare instances, those who proved themselves worthy, such as great warriors, were permitted to listen to the Storyteller's teachings.

The Tusken Raiders' history, as transmitted by Storytellers, was considered a single, indivisible narrative lasting hours to recite. Circa 4000 BBY, it detailed their entire known ancestry: their origins as the technology-loving Kumumgah, their enslavement by the Rakata, whom they called "the Builders," which catalyzed the realization of the importance of a connection with the land, their revolt against the Builders and the subsequent desertification of Tatooine, a long account of tribal wars and their evolution into a desert people, and finally the colonization of their planet by the Galactic Republic.

The translator droid HK-47 posited that these histories were likely created millennia after the events they described, resulting in a mythologized demonization of the Rakata that may have distorted the truth. For example, the Tusken perceived the Builders as an iconic force testing their ancestors' resolve, rather than the Rakatan race that conquered Tatooine. Furthermore, the histories claimed that the most arrogant and land-uncaring Kumumgah were exiled from Tatooine by the Builders, a story HK-47 considered fabricated and symbolic of societal cleansing through off-world enslavement. HK-47 also suggested resource depletion as an alternative explanation for the planet's desertification.

Traditional Tusken history asserts that their holy warriors drove off the Rakata oppressors through a heroic struggle following the planet's bombardment and desertification. However, HK-47 suggested that the Rakatans may have simply departed, believing their bombardment had "sterilized the problem."

The Tusken consider themselves integral to the land and deem anything separating them from it as sacrilege. This dictates their acceptance only of sanctified garments and banthas believed to retain a connection to the land. Any technology or clothing used by offworlders is thought to sever this connection and is thus considered sacrilegious. Consequently, they not only reject foreign technology but also violently attack anyone employing it on their land.

Tusken mythology also explained their hatred of outsiders, who reminded them of their past as the technology-dependent Kumumgah, either physically or socially. HK-47 suggested a lingering fear that outsiders were descendants of those tainted by Rakata abduction.

They believe that Tatooine's two suns were beings called the Sky Brothers, with the elder having attempted to kill the younger. His failure caused him to start a lifetime of running, his younger brother chasing him to kill him for his treachery.

Numerous rituals maintained Tusken society's cohesion. Many tribes tasked adolescent Sand People with a "bloodrite," where they demonstrated hunting skills by capturing a creature and fatally torturing it with techniques extending the pain for weeks before death. While most chose creatures like dewbacks or desert hulak wraids, the greatest prestige was reserved for those who performed the rite upon a sentient being. The most prestigious test of an adult male was to hunt and slay a krayt dragon, and retrieve a pearl from its stomach. Oftentimes, members of the tribe would create spirit masks out of natural materials for use in the ensuing ritual and celebration.

Additionally, Tuskens occasionally targeted podracers participating in the Boonta Eve Races, as a form of sport, a display of marksmanship, and retaliation for land intrusion.

A unique bond existed between Tusken riders and their bantha mounts. Upon a mount's death, the rider was often abandoned to wander the desert alone, trusting that the fallen bantha's spirit would guide them to a new mount if it so desired. Otherwise, the rider would perish in Tatooine's endless dunes. A Tusken returning with a new mount was highly esteemed by their tribe. This bond was reciprocal, with accounts of riderless banthas intentionally stampeding over cliffs. The rest of the tribe considered the unbonded individual to be pitiable, but did not scorn that person. Han Solo and Luke Skywalker witnessed the exile of one Sand Person who had lost his bantha in 12 ABY.

After slaughtering a tribe of Sand People in revenge for the death of Shmi Skywalker Lars, Anakin Skywalker became a legend. Depicted as a vengeful ghost or desert demon, the Tuskens made ritual sacrifices to ward him off, placing stolen artwork and valuables—even Human sacrifices, such as Kitster Banai—at the site of the massacre.

The Sand People communicated using a guttural language known as Tusken. Many individual names were lengthy and characterized by numerous stops, such as Grk'Urr'Akk, Grk'kkrs'arr, Orr Agg R'orr, Orrh Or'Ur and Orr'UrRuuR'R. However, shorter names like Sliven were also recorded in some clans, and some Tuskens, like A'Sharad Hett and his mother K'Sheek, bore patronymic (and perhaps matronymic) names formed from a parent's given name and a prefix: A' meaning "son of" and K' apparently meaning "daughter of."

Other known Tusken words include urtah (carrying pack) and urtya (light tent). Generally, Tuskens also possessed basic knowledge of Huttese and Jawaese due to frequent interaction with these languages.

When they still were known as the Ghorfas, the Sand People did use a form of logographic writing system, but it apparently fell into disuse with the decline of their civilization. The complex writing had degraded into mere crude symbols. Lacking a written language, the Sand People relied on oral history to transmit their legends and stories. Storytellers were thus held in the highest regard, entrusted with memorizing every clan member's story and piece of clan history. Apprentice storytellers faced immense pressure to precisely memorize these narratives, with a single mistake resulting in death. Successful recitation of a story led to becoming the clan's storyteller, while the previous one wandered into the desert, never to return.

During the Clone Wars, a Tusken language pack was marketed as an enhancement for protocol droids, enabling them to comprehend the Tusken language.

- Czerka 6-2Aug2 Tusken Cycler hunting rifle (long range)

- Gaderffii (mid-range)

- Hook-tipped Gaffi club (short range)

- Sand bat venom-spray (short range)

NOTE: Tuskens were known to customize their rifles with barbed stocks for melee combat; the barbs tend to be venom-laced.

The evolutionary origins of the Tusken Raiders can be traced to the Kumumgah, a technologically advanced race that once constructed grand cities across the then-lush world of Tatooine. Their space travel attracted the attention of the Rakatan Infinite Empire, who conquered Tatooine and enslaved the Kumumgah in 25,793 BBY. Sometime before 25,200 BBY, the Kumumgah rebelled against their Rakatan masters, but were punished by orbital bombardment and left for dead. The bombardment slagged the surface of Tatooine into little more than fused glass, which eventually crumbled into desert sand. The Kumumgah had anticipated such an act and survived by taking refuge in caves across the planet. Over time, they evolved into two separate species, Ghorfas, who would eventually become the Tusken Raiders, and Jawas.

The Ghorfa spent the next thousands of years as a nomadic society, attempting to come to terms with their new identity in a period they called "the long walk." After Tatooine was rediscovered by the Galactic Republic in around 4200 BBY, early Human settlers were believed to have disrupted the water-supply of a settled cave-dwelling society known as the Ghorfa culture, precipitating the transformation of the natives into the Sand People. By around 4000 BBY, they were also engaged in endemic low-level warfare with the settlers, raids which were among the factors that forced Czerka Corporation to abandon their attempts to operate Tatooine as a mining world.

Tatooine was, it seems, largely forgotten by the wider galaxy for the next few thousand years, and indeed, the planet apparently had to be formally rediscovered in 1100 BBY. By the sixth century BBY, however, a mining colony had been reestablished, and the key moment in the history of the Sand People and their relations with the outlanders occurred around 550 BBY, when they encountered an offworlder and rogue named Alkhara.

Alkhara initially served as an operative for the colony's Bureau of Ethnicity and Socialization, studying the Sand People and seemingly gaining their trust. However, he eventually betrayed the colonists, occupying the desert fortress previously used by the B'omarr Order and later by Jabba Desilijic Tiure's criminal empire. The extent of his banditry's connection to his relations with the Sand People remains unclear. In the most infamous incident of his career, he allied with a group of Sand People whose bivouacs lay on the Great Mesra Plateau to annihilate a police garrison, then turned on his Sand Person confederates, destroying their camp. This event is claimed to be the source of a subsequent blood feud between the natives and the outlanders.

Permanent settlement by offworlders—or outlanders—only seems to have resumed in 100 BBY, with the arrival of the settler ship Dowager Queen from Bestine IV. A new planetary capital called Bestine was founded, and a second settlement called Fort Tusken was established at the northern tip of the Jundland range. At first, the new colonists seem to have been unaware of the Sand People, but a series of attacks between 98 and 95 BBY forced the abandonment of Fort Tusken, and from that point on, the Human settlers of Tatooine referred to the natives as "Tusken Raiders."

Sometime after Biggs Darklighter departed Tatooine, considerable unrest arose among the Tusken Raiders, who raided even the outskirts of Anchorhead.

The initial appearance of the Tuskens was in the second version of the script for Star Wars: Episode IV A New Hope, where they functioned as Imperial intelligence agents organized as a military unit on Tatooine. Their mission was to find the reason Deak Starkiller had come to the planet. They were depicted as humanoid beings with red eyes, operating unique speeders. In the subsequent draft, they were reimagined as indigenous inhabitants of Tatooine.

The vocalizations of the Tuskens resemble the sounds made by Earth's sea lions, but Ben Burtt actually created their language using the sounds of donkey noises.

Within the Xbox game Star Wars: Obi-Wan, which takes place before and during the events of The Phantom Menace, Obi-Wan Kenobi, still a Padawan, is compelled to rescue who he believes to be Queen Amidala of Naboo, but it is actually Sabé, her handmaiden. She is kidnapped by Tuskens during a stopover on Tatooine. During the game, Kenobi is required to navigate a Tusken burial ground. As Obi-Wan, the player must follow the Sand People through their extensive canyon homes, which have been constructed from salvaged shipwrecks. Ultimately, the player engages in combat with a Tusken war chief who desires to keep the queen as a prize. A culturally significant moment occurs when the Tuskens, with solemnity and ceremony, accept their defeat after Obi-Wan demands safe passage with the queen, having triumphed over their leader.

Grave Tuskens are featured in Star Wars: Jedi Knight: Dark Forces II as followers of the Dark Jedi Jerec and Maw on the moon Sulon. This marks the only instance of a Sand People group appearing beyond Tatooine, although Hoar from Star Wars: Masters of Teräs Käsi did leave Tatooine to study martial arts from Arden Lyn. Additionally, in a frame from Crimson Empire II: Council of Blood, a solitary Tusken Raider can be observed within the palace of Grappa, a Hutt on the planet Genon.

Tuskens are present in Star Wars: Jedi Knight: Mysteries of the Sith during the Ka'Pa mission. While the level shares similarities with Tatooine, the game does not explicitly state the planet on which it is set.

Within the PC game Star Wars: Galactic Battlegrounds and its expansion, Clone Campaigns, there is an hidden surprise in the initial Chewbacca campaign. In the far right corner of the first mission, obscured by the fog of war, there is a scene reminiscent of the Obi-Wan mission described earlier. Accessing this scene requires the use of the cheat codes "forceexplore" and "forcesight" to eliminate the fog of war. Failure of this side mission results in the overall mission's failure.

The desert survival gear, a type of Sith stalker armor, bears a strong resemblance to the appearance of a Tusken Raider.

Republic 62 showcases a Tusken without their mask, although this depiction could simply be Anakin Skywalker's subjective perception of the Sand People rather than an accurate representation.

In the RPG Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, one of the optional quests involves the player infiltrating a Sand People settlement. Upon doing so, the player is presented with a potential historical background of the Sand People.

The game suggests the possibility that the Kumumgah, along with the Tusken Raiders and the Jawas, may actually be Human, or at least related to them. During a conversation with the clan's narrator within the Sand People's village, if the protagonist, Revan, inquires whether the similarities between those taken by the Rakata and the Human colonists are physical or societal, HK-47 will caution, "Warning: Master, if you intend to propose that humanity shares ancestral ties with ancient Tatooine, you will push his belief system to its fragile organic unit limit."

At one juncture in the game, HK-47 refers to the storyteller as "this Raider." The term "Tusken Raider" would not be formally established until nearly 4,000 years after the game's setting in 3956 BBY, but the word "raider" simply denotes someone who raids, and Fort Tusken is not mentioned.

In the novel Darksaber, Luke Skywalker comments on the difficulty of distinguishing between Tusken males and females, yet in Attack of the Clones, distinct differences in attire are apparent between the sexes. However, these sartorial distinctions were not yet established at the time of Darksaber's publication.